Civic Revival founder Peter Stonham questions the thinking behind ‘grand designs’ visions that seem to be regarded as the only way forward for every town. He examines both the underlying concept and the deeply flawed way in which developers, planners, architects and local authorities all sign up to Masterplans which fail to reflect the true aspirations and values of the communities they are supposed to benefit. And do great damage to the character and distinctiveness of individual places.

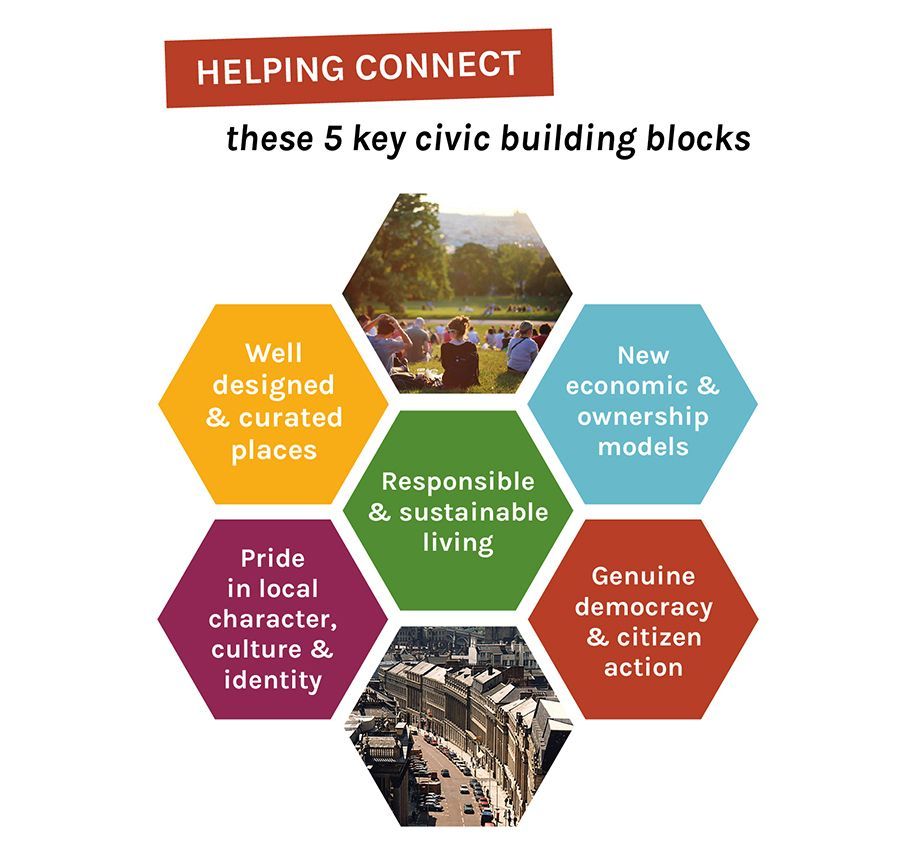

A thoughtful civic approach to the future of society is made up of more than one dimension. A glance at our original Civic Revival concept diagram indicates five overlapping important elements that come together to underpin a thriving and positively regarded area. These are well-curated Places; recognition of Character; quest for Sustainability; innovative Economic activity; and true expression of Democracy.

You’ll notice that there isn't one of those blocks specifically covering the subject of ‘planning’. And in my belief, planning in itself should not be one of the core building blocks. Planning is something you do to achieve what you want. And when planning is done, it needs to be a servant, not a master.

Sure, planning is always needed, to ensure emerging issues and challenges are addressed, and to guide and control what is allowed to happen in the interest of everyone; not just property owners, for example.

Unfortunately, we live in an age where a particular type of planning – the concept of Masterplanning – has become the big thing to be pursued relentlessly by supposedly dynamic local authorities. And I want to consider here how this had happened, what it means for us all, and whether we really like it or not that way. Indeed, having spent some time looking further at the subject, and considered my ideas on it, I've decided I don't actually like Masterplanning – and I’m not sure it’s good for us at all.

Nearly a hundred years ago the great psychologist and founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud wrote a book called ‘Civilization and its Discontents’, and that title resonated with me in thinking about Masterplanning. There's no straight parallel, but there are a few similarities in his thinking – particularly about matching individual and collective expectations in society.

Freud’s book was written in 1929 and first published in German in 1930 as Das Unbehagen in der Kultur ("The Uneasiness in Civilization"). It explores what Freud sees as the important clash between the desire for individuality and the expectations of society, the book is considered one of Freud's most important and widely read works.

While I don't think we can deploy Freud’s thinking directly, or have anyone from his field of professional observations to help us in looking at how we plan the future of our towns and cities, I’m taking as my starting point the idea of a clash of expectations breeding real discontent with the way we do things, and a consequent failure to address the proper needs of civic society. A case I put in sadness, and some anger and concern, at the way in which a conflict between the community and self interestedness (and often ego) has become an effective conspiracy by the property sector, along with the planning and architectural professions and many elected authorities, to irreparably damage our collective built environment.

A little bit of personal experience may be relevant here. I live in Hastings – which is one of the two founding locations for Civic Revival. It's quite a delightful South Coast town with eccentric buildings and street layouts, with a lovely history of many different eras. Including, for some historical, wonderful accidental reason, it ended up with a cricket pitch – the Central Recreation Ground/Priory Meadow – in the middle of the town centre, with the ‘normal’ shopping and civic areas effectively wrapped around it.

This distinctiveness made it quite difficult to plan the retail and the commercial activities of the town, but the setting around the cricket pitch was an unusual, and, to me and many others, a delightful, way of organising a town centre. But sadly it couldn’t survive the last decade of the 20th century, and someone’s greedy eye landed upon this wonderful possible (and demonstrably greenfield) development site. You probably don't need me to tell you the rest of the story.

With the site sold on, and no cricket pitch of course there now, the outcome was that we've ended up with a shopping centre on the cricket pitch, and a last token batsman frozen in time there as a statue, a mere sop to the history of this area, and the fact that we once had this delightful unique cricket pitch in the town centre.

The other town that is the anchor location for Civic Revival’s origins is my colleague Richard Walker's hometown of Bolton. So let me also tell you a bit about Bolton. It’s a Victorian industrial town, of course, which has changed much since its heyday, but if you see a picture of Bolton in the 1950s it shows a rather peaceful, not very traffic-heavy, but busy and simple Town Centre environment, which a lot of UK towns would have had at the time.

You can obviously see from the photo there was some 50s redevelopment, but significantly older and historic built environment comfortably sitting alongside it as well. Sadly, if you go forward the next half-century, you’ll see that much of this atmosphere has disappeared, including various demolitions and a significant bland piece of redevelopment done in the 1970s/80s. But even now they can't leave the town alone. And so there's going to be another demolition job and redvelopment.

Originally intended to happen last year, it was a familiar wheeze to bring something new to the town centre – but something highly stylised and standardised from the developers’ much overused playbook, which I'm not at all sure is coming to meet the wishes of the citizens, but rather of the investors: in this case a a development consortium called Bolton Regeneration Limited and made up of Chinese firm Beijing Construction Engineering Group International, the Department for International Trade, and the Greater Manchester Combined Authority – and is being led by Midia (an investment and development specialist).

Hastings and Bolton are hardly unusual in their experience. Another example of such unwelcome change is currently happening in Crewe. It’s current, or rather, up-to-now current, town centre precinct was not a perfect legacy of the town’s railway history, but a modernist brick-built though relatively gentle design that was put up in the mid 1950’s.

Unfortunately, in the years since, it has been affected by changes in retail activity, and been allowed to decline and get into a poor state. So it became the mission of the East Cheshire District Council to ‘do something to improve the town’ by replacing it with a spanking new ‘modern’ leisure & retail development hatched with a property company in a deal which nobody in the town quite understands, or much likes. It certainly owes little to the character and heritage of Crewe, and more to someone’s wish to get a return on a property development. Regrettably, the aspiration to ‘make a bold step forwards’ has taken over, and has meant that in the last few weeks the existing centre has been put under the wrecker’s ball with no certainty at all about what will take its place.

It seems yet another tragedy to me. Our Civic Revival friend Chris McGarrigle, who lives in the town and understands these things from his position as a chartered surveyor, certainly believes that something that, with imagination, could have played a continuous role, has been destroyed for no good reason. And he’s absolutely of the view that the bombsite that's now been created is actually not going to become anything else at all anytime soon. So there will be a black hole in the centre of Crewe for many years, and a new desperation to build something – anything – on it.

In most professional opinions, the developer’s scheme is just a fantasy. It’s surely also a highly questionable view that a cinema and a bowling alley plonked in the town centre to a template design is really what the town needs, especially when cinema is now in decline. But someone's hatched that plot, and unfortunately, it's led to the wipeout of the existing Town Centre, enthusiastically endorsed by East Cheshire District Council.

So my key question is, in the light of the Hastings, Bolton and Crewe stories – and very many others – why do we keep smashing up our shared cultural and social inheritance in pursuit of some externally driven conceptual vision, which is not often what the local people want, and is being done by an impetus to a plot they are seldom allowed to really understand. The stories of Hastings, Bolton and Crewe are not at all unusual, and the outcome has become what has been known as ‘clone towns’ – places all with the same kinds of architecture, layout, retailers and ’public realm’, made up of bits of the same urban placemaking lego set too.

As I prepared this article, I wondered if I am the only one who is not totally in love with this idea of ‘Masterplanning the Future’. So I did a bit of googling, and I actually found only one other professional view that really resonated with my own. Most of the professionals; politicians and media just seem to accept this approach as a wholly good thing. The only clear dissenting voice was that of maverick architect Christopher Alexander, who I must admit I hadn't really studied that closely until the last few weeks. But if you read what he says, it soon becomes obvious he is one of the few architects who's not batting for the primary role of his profession in quite the way most do. His view is that we need to be much more subtle and much more sensitive in the way we come up with development schemes for our towns and cities. He invented an idea called pattern recognition, which is a way of looking at the existing form and the existing character of somewhere and running with it, rather than blasting it away with a new scheme.

Here’s another of of Alexander’s very insightful quotes:

“High buildings have no genuine advantages, except in speculative gains for banks and land owners. They are not cheaper, they do not help create open space, they destroy the townscape, they destroy social life, they promote crime, they make life difficult for children, they are expensive to maintain, they wreck the open spaces near them, and they damage light and air and view.”

I’d say he’s not the greatest fan of Masterplanning.

With all this talk about Masterplanning, you probably want to know what it actually ‘officially’ means. It's a bit suspicious, in fact, that the best definition I could find was from the World Bank – a body more likely to favour development than conservation.

Here’s how the World Bank puts it:

“A Masterplan is a dynamic long-term planning document that provides a conceptual layout to guide future growth and development. Masterplanning is about making the connection between buildings, social settings, and their surrounding environments. A Masterplan includes analysis, recommendations, and proposals for a site’s population, economy, housing, transportation, community facilities, and land use. It is based on public input, surveys, planning initiatives, existing development, physical characteristics, and social and economic conditions.”

Taken at face value, this seems to be a very idealised and wide-ranging idea of how Masterplanning is actually being done, why it's done, how it should be done, and what it leads to. It’s pretty clear that it is not always carried out that way.

Whatever the theory, Masterplanning has, over the last fifty or so years, been embraced across virtually all the related professions: planners, architects, urbanists and surveyors; and also apparently recognised by political leaders, nationally and locally, as generally an unquestioned wonderful thing, we all need to do everywhere. And the media is generally onboard too, loving stories about new schemes ‘to re-cast run-down town centres’ as one of the memes of the age – whatever might be lost in the process.

If the theory might be treated generously as at least in some ways well-intentioned, I think the practice is very different from the theory. And I've made my own a four-point narrative, which I think explains more accurately what's actually happening in practice these days.

It goes like this:

Stage 1

Councils are sold a vision of modernism and economic prosperity to be achieved by ‘investment’ in their area, and adoption of the latest stylistic designs – which require large footprint sites to be made available for developers to build upon. Quite often, their plans will strongly feature international architectural tropes, which you see over and over again in glamorous cities around the world, and which leaders invariably want to have in their own small town too, appropriate or not.

Stage 2

Prospective developers co-opt the council into their ‘vision’, and work with planning and architectural advisors to create a suitable glossy and impressive Masterplan, justified by the use of conceptual maps and borrowed images from other cities around the world to show just how wonderful a place the town could become.

Stage 3

The council becomes the lead advocate of the scheme, which the developer has notionally signed up to, but no one sees the full documentation and all the escape clauses and conditionality that will allow the project to be abandoned if all sorts of criteria fail to be met, including the commitment of anchor tenants, suitable economic conditions, and necessary commercial viability.

Stage 4

The existing buildings and public spaces are allowed to decline as ‘they won’t be there for much longer’ because the new scheme is coming. Sometimes Compulsory Purchase Orders (CPOs) are used and existing occupants evicted. And, often, demolition becomes the favoured option as the last available ‘declaration of intent’ by the ‘authorities’ that something better is coming soon…

Whether it’s London, Manchester, Mansfield, Middlesbrough or anywhere else, the ‘powers that be’ all seem to want the same thing. The council officers and elected members invariably become the advocate of the ‘Masterplan’ vision and the concepts put forward by the property and planning professionals which the developer has only notionally signed up to anyway – with no guarantees it will be ever built. Under the cloak of ‘commercial confidentiality’, no one sees the full documentation that underpins the project and the ‘deal’.

So the key outcome is that the council and the developers end up in bed together. And the council becomes committed to a vision which the developer will only do if the right circumstances arrive. And they very rarely do. At worst there’s no scheme implemented – or further unwelcome changes are negotiated to ensure it is viable – and at ‘best’ the originally intended and mass produced new retail complex lands in the town centre as if from another planet, turning it into Anywheresville.

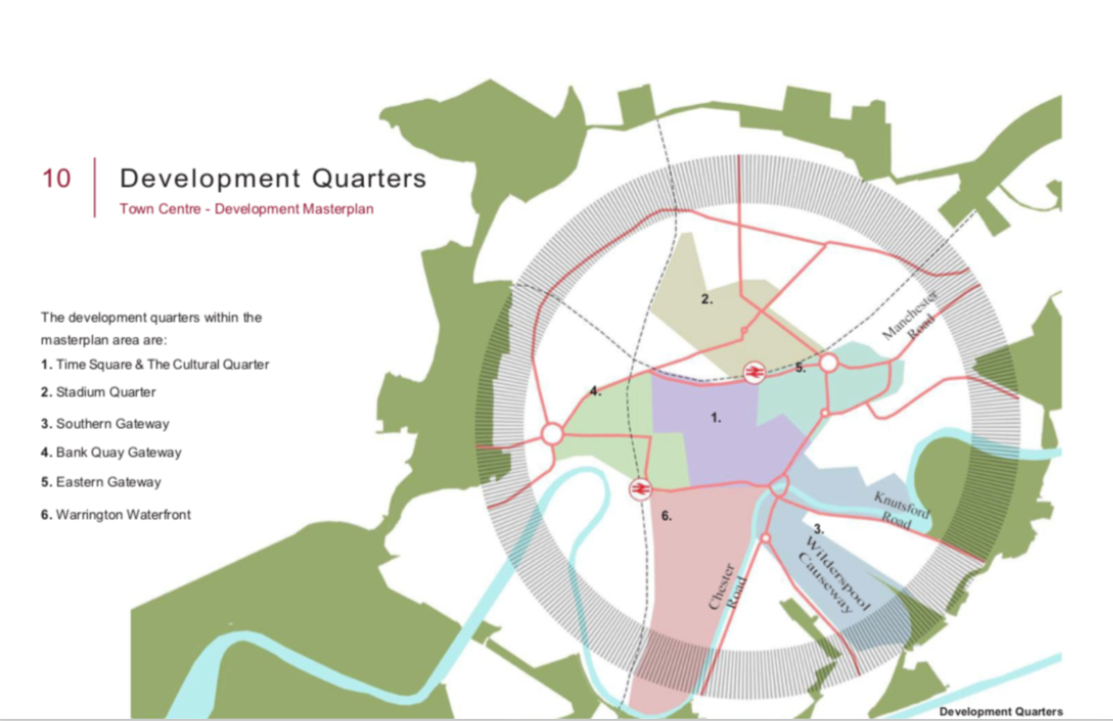

I believe this strange, unwelcome, uninvited way of thinking seems to now be a virus that has infected large swathes of the country. From just a quick check online the other day, I found dozens of such examples at various stages of progress around the UK. One of the latest, and most scary, is Warrington’s new Masterplan produced by consultants, endorsed by the District Council, but now opposed by the seven town councils that make up the ‘second tier’ area below Warrington District Council.

It's an all-embracing re engineering of the town with demolition and redevelopment to create all the white buildings on the 3D illustrated map. And it's got the usual formulaic idea of creating new “quarters”, which seems to be the thing of the day. Indeed, every town has to become ‘drawn and quartered’. I think it's partly because such quarters make large lumps for developers, and are easy to label for marketing purposes. This cauterization of everywhere seems to be almost a core thinking for these Masterplans.

Refreshingly, and a cause for hope, the seven opposing town councils resolved to challenge the plan, led by Cliff Taylor, Councillor for Grappenwall and Thelwall Parish. They have recently made a delightful statement of a new way of thinking, and unveiled their own alternative plan at the end of October. It’s titled “a new plan for a changing world”. Done with very limited resources it’s pretty sketchy and very generalistic. But it takes a completely different starting point to the one in this grand Masterplan that they're not happy with. They’ve even made a video setting out their alternative thinking:

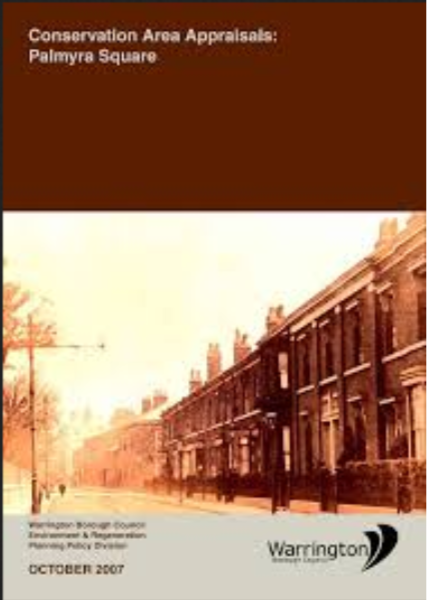

What has made the District Council so keen on this ‘Masterplan’? It didn’t used to think this way. I found a document from Warrington Council prepared only 14 years ago, which was a council assessment of the town’s conservation area. What a contrast. It was so fine grain. It's a rather wonderful thing to read as it's so detailed. There's so much history recognised, and the authors have clearly researched all the character and all the reasons for the things that were there in a document which is so much more full of spirit, and pride in the specialness of Warrington, than the Masterplan that has just been done by consultants seemingly determined to make Warrington look like everywhere else.

So much of this kind of thing is still going on. There's a lot of places getting demolished to make space for ‘wonderful new things’ As we speak there are schemes for Stockport, Bolton, Basildon and Winsford, Lewisham, Nottingham and Stockton – and plenty of others too. The photo of Reading below shows the sort of site that development demolition creates. And it's awaiting the sort of scheme that I'm sure in the current real world, we will wonder for a long time if it's ever going to arrive.

A few such projects do get a bit more critical analysis as they get stuck. In this regard, it is worth name-checking here the Bishopsgate, Elephant and Castle and Croydon Westfield projects in London. Once upon a time we thought at Civic Revival that we should concentrate on problems and opportunities around the country in areas that were suffering and in need of help, rather than in London, which was better characterized as having an overheating economy and being the cockpit of globalised thinking. But London is rather different now since Covid, and is becoming as needy in this regard as everywhere else. The glorious prosperity days of London do now seem to be potentially over and the blighted projects mentioned are leaving a very similar urban nightmare to places all around the country.

The Elephant and Croydon schemes have been effectively abandoned with the relevant Councils desperately casting round for alternatives, and in Croydon's case, in a financial mire through its over-ambitious and naive thinking about redevelopment. It too now has void sites scarring the town centre after presumptive demolition.

So let me now summarise the case for and against Masterplans. Yes, they're visionary. They're groundbreaking. They're modern. They demonstrate that councils are ‘doing something’ for the area. They're strategic. They generate lots of building work for, first, demolition, then reconstruction.

But my case against them is that they're prescriptive, arrogant, and assumptive. They're overconfident. They generally destroy the familiar and cherished. They're inflexible. They're frozen in time. And because they generate excessive building work and demolition, they're very eco-unfriendly.

And worse than all that, they embody highly unhealthy relationships between local authorities, professionals and developers from which most citizens are effectively excluded, and which many citizens find it very hard to know about and to investigate and to even comment on.

People once felt that council planners were doing bad things and not necessarily following the interest of the places and the people that they were supposed to be working for. Now, whether misguided or not, these planners have been mainly neutralised and it is the developers who are really the reason such things are happening. So it's not the planners you should blame really. It's the developers, having courted the planners and the councillors into their plot (perhaps without them even knowing it)...

It’s a sad story, but I think that more and more people involved in civic activism are realising that it’s simply no good people having positive views and aspirations for a local area, when the greater need is to recognise that the way the system works and the changes that must be made to the process, and the actions of the various players within it, to avoid continuous repetition of the outcomes that we invariably so much regret.

Peter Stonham

Footnote

I know that some others have made a similar analysis to mine. Those like Francis Northrup, who is a fellow at the New Economics Foundation have been working on a project called Democratising the High Street, which is due to be published in the New Year. Their interim findings are already that the core problem behind what I’ve described is what we might call an ‘extractive system’ where the only purpose of development is to make money out of development projects. The local community doesn't actually get much benefit from it at all, as all the profit is extracted out. This process is also well understood by those who have studied in detail what’s happening in those high profile places in London like Bishopsgate - chronicled in depth by the Bishopsgate Goodsyard: Stop the Monster campaign - the Elephant and Castle and Croydon (Whitgift Centre). See particularly the Master's thesis by Steve Taylor about the plans for the Elephant and Castle by developer Delancey, leaving the existing shopping centre boarded up and blighted, and the money flows that would result from the development.

Also well chronicled has been the process as applied in Bradford over the past couple of decades, where a planned development led to a cleared site lying unused for ten years, and when it eventually opened, sucked the remaining heart out of the existing city centre.

I’m pleased that this discussion was also at the core of our third Civic Revival online forum, the recording of which you can view on this site along with a detailed summary of the contributions made, including my presentation based on this feature.