Dr Nick Wates reviews his 40 plus years of working to involve communities in the future of the places in which they live and work – and the lessons he’s learned

I’ve spent the best part of my working life seeking to empower local people to shape and look after their own areas, and resist big battalions with alien, unsympathetic and unwelcome ideas about what should happen there.

Earlier this year the University of Brighton awarded me a PhD by Publication for five books I produced with many collaborators over a period of almost half a century. The thesis I submitted, Making Places Better, explains the context:

‘This document is an argument from an urban activist in the second half of the twentieth century and the first years of the twenty-first. A campaigner for better neighbourhoods, cleaner air, green spaces, connected transport, proper recycling, better housing and, above all, more involvement by local people in decision making about their local environment. The author campaigned, worked and created homes in neighbourhoods in central London (Tolmers Square), London’s docklands (Limehouse) and a historic south coast town (Hastings) helping to lay the intellectual and practical groundwork for what has come to be termed ‘placemaking’. It can now be seen that the author was part of a broader emergent movement practicing urbanism differently. He collaborated with local residents, journalists, academics, professionals, politicians and institutions of many kinds in the UK and overseas on what can best be described as ‘action research’ or ‘participatory action research’.’

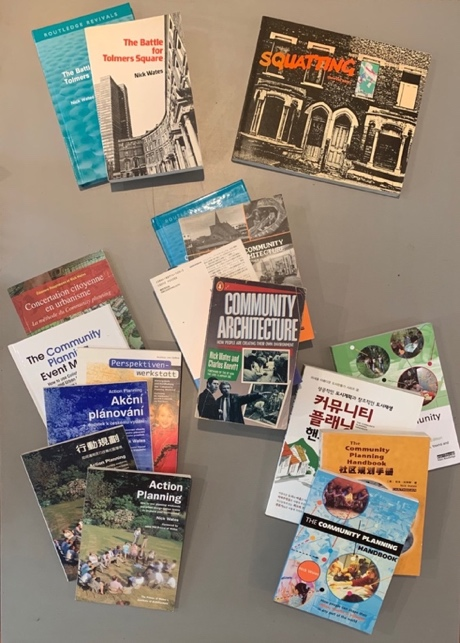

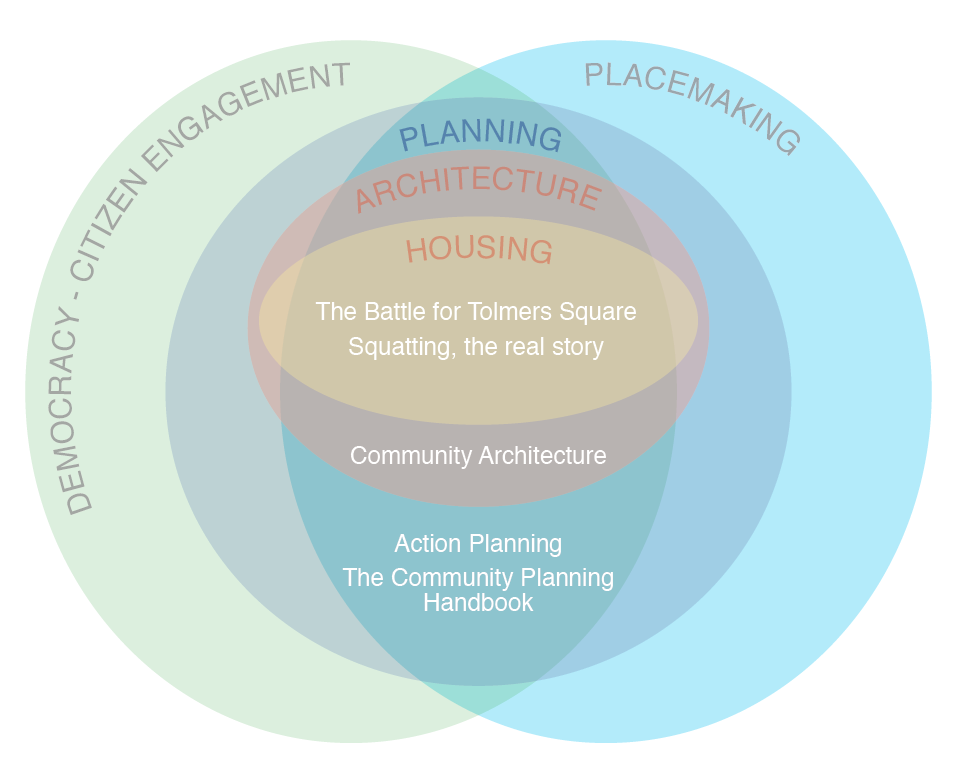

Alongside articles, films, radio, training sessions and presentations, the main legacy of my career as an author and practitioner has been five books: The Battle for Tolmers Square; Squatting, the real story; Community Architecture; Action Planning; and The Community Planning Handbook.

Rather to my surprise, I discovered from mainly online research the following about the impact of my five publications:

- They have received at least 101 reviews in magazines and newspapers and been the subject of 16 radio interviews;

- They have been cited in 882 books or journal articles by other authors and academics;

- They have led to 45 invitations to speak at conferences or facilitate workshops in the UK, and 26 overseas;

- Nine foreign language translations have been produced, three of them adapted with additional local material;

- Two of the books achieved second editions, at the request of publishers;

- Powerpoint presentations based on the books have received 27,900 online viewings.

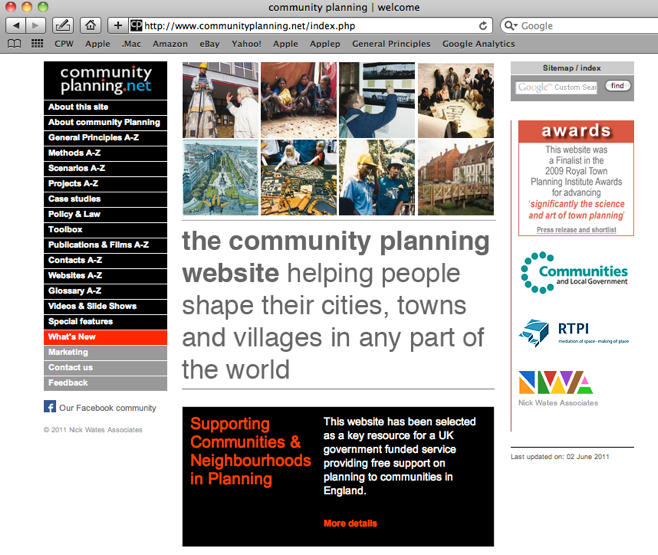

In addition, Communityplanning.net, which started life as an online version of The Community Planning Handbook,

‘has consistently been Google’s No 1 result for a search on ‘community planning’. In the last ten years alone over a quarter of a million people have visited the website and collectively spent a total of 706 days looking at its content. Although the majority of users have been from the UK and USA, the audience has been truly international; from all parts of the inhabited world.’

It is not easy to summarise five books with a total of 375,384 words and 1,125 illustrations, but some extracts and reviews provide a flavour of the books and their main messages, which I believe can still help, encourage and support those campaigning for better places, and a richer civic life.

My writings began with the record of a sometimes celebrated achievement of preserving part of an appealing and much-loved yet ordinary piece of inner London against tough odds.

The Battle for Tolmers Square (1976)

The introduction is youthfully direct, and though written over 40 years ago, still has resonance today:

‘Britain’s cities are in chaos. While thousands of houses stand empty there are not enough homes for people to live in. While acres of land lie derelict, many thousands of building workers are unemployed. Transport is congested and inadequate, and unemployment in the city centres is higher than the national average. Yet whole areas are still being destroyed to make way for office developments, which frequently have little social value, and merely exacerbate the problems.’

A review of the book by John Lord when it was reissued in 2013 concludes:

‘More than 35 years on from the events it describes, The Battle for Tolmers Square is still a gripping read…. Aesthetically, the book is a period delight: a dense collage of text, grainy photographs, plans and graphs. It looks and feels like a piece of agitprop rather than an academic text. That is entirely appropriate for a book which, written by a soldier in the ‘battle’, is not afraid to take sides…. Apart from reviving memories of an important but long-forgotten episode in the history of modern London, this valuable and entertaining book is most notable for its candid and nuanced insider’s view of the campaign to save Tolmers, and especially of the dynamics of community relations.’

By 1980, I had turned my attention directly to the housing crisis – and the concept of direct action by people seeking somewhere to live.

Squatting, the real story (1980)

The Introduction starts like this:

‘Since 1968, over a quarter of a million people in Britain have walked into an uninhabited house owned by someone else and proceeded to set up home, without seeking permission and without paying rent. By doing so, they have become squatters. Some have been thrown out within hours. Others have stayed for months, even years, before being evicted by bailiffs or leaving under threat of a court order. A few have managed to establish permanent homes.

Most squatting has occurred in old flats and houses in the larger towns and cities, but every conceivable type of empty property has been squatted — from luxury flats to dilapidated slums, from country cottages to suburban semis, from old churches to disused factories.

Squatting is an ancient practice, and has occurred at some stage, in different forms, throughout the world. Yet the last 12 years in Britain has seen a spectacular rise in the number of people who have taken over empty buildings. No longer does “squatting” describe the isolated actions of numerous individuals. Instead, it has become a social movement of great significance, whose impact upon housing policy has already been considerable, but whose potential has yet, perhaps, to be fully realised.’

A review of the book on Amazon’s website in 2011 by Tony Gosling under the headline ‘Classic selling for over 20 times its original price’ concluded:

‘A valiant effort to ensure that history is not entirely written by the rich & powerful. Using a mixture of press cuttings and their own reminiscences & photographs the authors successfully pull together much of the motivation and the lessons learned from mass squatting in the 1970s and before. But it is the humour that makes this book an absolute classic … it is squatters' indefatigable resourcefulness, turning abuses of their basic human rights by greedy landlords into a satirical pop at their abusers, and even into verse, that makes this a classic tale of the triumph of the underdog. Yes the landlords have the full force of the law on their side, but somehow the squatters almost always come out on top strolling off down the road to populate another empty! The moral winners kicking sand in the face of the rich people and authorities booting them out in the street. With present and past squatters as well as the public spirited but more conformist members of society this is the sort of book that William Caxton invented printing for – a visionary tome that speaks of a better world to come where all of Britain's sixty million people have somewhere to call their own.’

In the late 1980s I looked at the vogue for ‘big development’, and how it failed ordinary people, focusing on professionals working with communities in a better way and the London Docklands ‘regeneration’ plans.

Community Architecture (1987)

A powerful critique of the status quo can be found in a chapter called ‘cities that destroy themselves’ following an account of 1980s life in Limehouse, supposedly part of the flagship docklands development:

‘Despite having a proud and distinguished history, a strong community spirit, a distinctive character, some fine buildings and natural features, and some exceptionally resourceful community groups, Limehouse in 1987 remains lifeless, resembling a morgue rather than a city….

People living in and working in Limehouse – as elsewhere – know by and large what they want and what needs to be done. Instinctively. They know because every day they experience the problems and understand what is wrong. They know, for instance, where it would be useful to have shops or play facilities; they know that a new footpath in a certain location would mean they no longer had to walk along a fume-choked pavement within inches of juggernaut lorries. Furthermore, many of them have skills which would enable them to help with the community’s problems and bring it back to life.

Yet those with the power and resources to influence events in Limehouse are not drawing on this wealth of talent and understanding when they make their plans. Apart from a handful of owner-occupiers (less than 5 per cent of the population), none of the people who make decisions about land and property in the area live or work there. There is no way for local people to influence events. And when they try to take the initiative, they run up against insuperable obstacles. They cannot improve their own homes because the landlords’ rules forbid it, and in many cases the buildings are so badly designed that they require major reconstruction. They cannot build new housing for themselves because they cannot get any land or raise finance. They cannot start up new businesses because there are no suitable small and well-serviced premises available. All initiatives, both individual and collective, run up against bureaucracy and inertia. Confrontation takes the place of sensible discussion. Frustration breeds a sense of hopelessness, apathy and despair.

Technical solutions to all the problems in Limehouse exist and have been employed successfully elsewhere. The housing estates could be re-designed to make them pleasant places to live. The derelict basement carparks could be put to other purposes, such as workshops or music studios. Unused pockets of land could be turned into parks, gardens or playgrounds: the filthy canal could become a pleasant recreational amenity. The area has great potential. But the inhabitants have no way of putting these ideas into practice for two fundamental reasons: they have no access to the technical assistance necessary to turn ideas into reality and they have no effective form of neighbourhood government through which to coordinate the community’s affairs.….

None of this state of affairs can be blamed on any particular individual officers or members of the various authorities involved, or on professionals per se. Many of them are equally frustrated by the state of paralysis. But they have not been trained to deal with it and are unable to find a framework of employment which would enable them to apply their skills creatively with, and in the interests of the people of Limehouse. Many talented planners, architects and designers actually live in Limehouse but can only find employment building office blocks and luxury housing outside the neighbourhood. All parties are simply locked into a system which has ceased to function.

The re-development - or rather mal-development – of Limehouse is not addressed to any community, past, present or future. It is not guided by knowledge, history, vision, theoretical analysis or practical experience. Neither is it based on open and rational discussion, weighing the evidence or reasonableness. At every level – from the management of individual homes to the planning of the neighbourhood as a whole – it is simply an architecture of neglect, short-sighted expediency and stupidity.’

And the solution?

‘The key is to get the process of development right: to ensure that the right decisions are made by the right people at the right time. And the main lesson to emerge from the pioneering projects (and backed up by an increasing volume of theoretical research) is that the environment works better if the people who live, work and play in it are actively involved in its creation and management [original emphasis]. This simple truth – the core principle of community architecture – applies to housing, workplaces, parks, social facilities, neighbourhoods and even entire cities. And it applies to both capitalist and socialist economies, whether rich or poor.’

In an online comment to an obituary for my co-author Charles Knevitt in 2016, Architect Ben Derbyshire (later to become President of the Royal Institute of British Architects) wrote:

‘Charles Knevitt and Nick Wates' Penguin book, Community Architecture defined the spirit of an era when many were trying to re-orientate architectural practice on the basis that an environment designed with the input of its users would be more sustainable. Dismissed by many at the time as an abdication of the architect's responsibility, many of the principles subsequently became mainstream. Charles and Nick were vitally important culture carriers for many of us at that time and helped establish community architecture as a legitimate presence in the RIBA.’

By the mid-1990s my mission was to produce how-to toolkits on genuinely involving communities in shaping their own futures.

Action Planning (1996)

Action Planning was the first product of a research programme to develop and distribute best practice at The Prince of Wales’s Institute of Architecture called ‘Tools for Community Design’. The book’s introduction explains:

‘Action Planning is a new technique of urban management which has already been practised to great effect. Instead of relying solely on private initiative and bureaucratic planning procedures, strategies for action are generated by getting all interested parties to work together at carefully structured events - normally lasting 4 or 5 days - guided by a multidisciplinary team of independent specialists.’

Prince Charles in his foreword writes:

The practice – and art – of Action Planning is still very new. I am delighted that my Institute of Architecture is publishing this first handbook to help people grasp the immense opportunities offered by this valuable technique.’

Reviewing the book, partnership expert Ros Tennyson described it as:

‘A unique guide to the whole process of Action Planning, particularly suitable for those new to the concept and who have a desire to take action for themselves….Clearly and attractively set out, the book is a joy to handle – the size, weight and layout all contribute to its being a truly handy reference guide which encourages you to use it. The text is simple, direct and unpretentious, and makes great effort not to get bogged down in intellectualising…. Its value has been proven in the field – most recently in Kazimierz, Krakow.’

I followed up ‘Action Planning’ with The Community Planning Handbook (2000), a comprehensive overview of how people can shape their own environments in a range of situations in the UK and around the world.

The introduction of the Community Planning Handbook spells out the philosophy of community planning and my view on the state of play:

‘All over the world there is increasing demand from all sides for more local involvement in the planning and management of the environment. It is widely recognised that this is the only way that people will get the surroundings they want. And it is now seen as the best way of ensuring that communities become safer, stronger, wealthier and more sustainable.

But how should it be done? How can local people – wherever they live – best involve themselves in the complexities of architecture, planning and urban design? How can professionals best build on local knowledge and resources?

Over the past few decades, a wide range of methods has been pioneered in different countries. They include new ways of people interacting, new types of event, new types of organisation, new services and new support frameworks.

This handbook provides an overview of these new methods of community planning for the first time in one volume….

The methods described here can each be effective in their own right. But it is when they are combined together creatively that community planning becomes a truly powerful force for positive and sustainable change….

In years to come it is possible to imagine that every human settlement will have its own architecture centre and neighbourhood planning offices; that all development professionals will be equipped to organise ideas competitions and planning weekends; that everyone will have access to planning aid and feasibility funds; that all architecture schools will have urban design studios helping surrounding communities; and that everyone will be familiar with design workshops, mapping, participatory editing, interactive displays and other methods described in this book. When that happens, there will be more chance of being able to create and maintain built environments that satisfy both individual and community needs, and that are enjoyable to live and work in.

In the meantime the art of community planning is evolving rapidly. Methods continue to be refined and new ones invented. There is a growing network of experienced practitioners. This handbook will hopefully help with the evolution of community planning by allowing people to benefit from the experience gained so far and by facilitating international exchange of good practice.’

Rob West, Senior Commissioning Editor at publishers Earthscan wrote in 2006 about this author’s most popular book:

‘By virtue of its high quality and reader-friendly usability, The Community Planning Handbook has proven to be one of our most successful publications and the response from buyers has been nothing short of astounding.’

So why does any of this matter today – and how can it help those working for a new civic revival that gives ordinary people much greater control over, and ability to contribute to, the wellbeing of their towns and neighbourhoods? Surely it was all a long time ago and things have moved on?

Yes, things have changed, but not always desirably and many battles still need to be won. As we contemplate a post pandemic world, there is much talk about doing things differently. Participatory planning can be an important ingredient in that; for making places better and for making places better. For both endeavours it is essential to learn from experience gained on the streets; working in real places, with real communities, in real situations. My books record some small parts of the jigsaw that is always incomplete. There are many more pieces yet to be discovered as places are continually being made and remade and we learn to share our successes and failures ever more effectively.

© Nick Wates, 2020

Nick Wates is semi retired and living in Hastings. He welcomes collaborating on interesting projects but is enjoying spending time on his allotment and building websites. More information on his website www.nickwates.com from which you can download free his doctoral thesis 'Making Places Better'.