by Jessica Prendergrast of Onion Collective

Jessica Prendergrast is a director of the Onion Collective, a social enterprise developing community-based regeneration projects in Watchet, West Somerset, and offering consultancy services on the basis of the belief "that every community has the power to build a strong and secure future for itself."

Jessica has kindly permitted Civic Revival to reprint this essay on 'Attachment Economics', as published on Medium here. This substantial essay discusses many of the themes that Civic Revival has been following for the past year, and crystallises some important new concepts for civic activists and the new economy. West Somerset is close to our hearts at Civic Revival, as it is where the first discussions about setting up the project took place, as discussed in one of the Civic Revival website's original posts, here.

Attachment Economics: everyday pioneers for the new economy

by Jessica Prendergrast

With politicians this week either delighted or reeling from last week’s election results, heads are once again being scratched about what on earth is going on in voters’ minds and from where economic and political change will come. In this paper, the precursor to a publication which is being written by some of the most inventive community entrepreneurs in the country, I explore the challenge of creating a new economic story from the ground, rippling up from the ‘bottom’, from the experiences in communities but capable of reaching outwards and upwards. The appeal to ‘community’ rather than ‘local’ narratives is intentional — this is a story told locally but it is not primarily about local government. Rather, it is one about people, as workers, employees, employers, but also as members of a community, or many communities, and their relationship to the economy — national or otherwise. It is a narrative found in post-industrial, rural, and peripheral places and in deprived, down-trodden, urban ones — all those where a national fiction of technological advancement and trickle-down wealth is all but irrelevant to everyday life. It reflects the emotion, action and conversations in those places which are often referred to as ‘the left behind’ but which can perhaps be better conceived of as ‘pointing the way forward’ — the places within which the pioneers of the next economy are already emerging.

It is primarily a story about relationships — between the individuals and the state, between communities and the market, between political structures and economic life. But for forty or so years, the dominant mode of interaction between these structures has become increasingly transactional not relational. Questions that are primarily about connection, attachment, association and entanglement, have been answered through a conversation that is individualised, servicised, consumerised. Our interactions with the state, the market and even the infrastructure of civil society have lost their communal flavour. We remain deeply attached — a feature of our human nature as social animals — but our politics, and more importantly, our economics, have become detached from who we are, what we need and what gives us security, meaning and agency.

Four particular problems dominate and intermingle in the discussion — all externalities created by the prevailing system. These are: rising economic inequality that is undermining a sense of fairness; structural racial inequity that is compounding the division; an impending climate catastrophe in which the current economic system is degrading the planet beyond its limits; and the destruction of belonging in our communities. The arguments about increased inequality hardly need to be rehearsed — social and economic inequalities and personal precarity continue to grow, shaped by complex, interrelated and messy trends from deindustrialisation to automation. The result is a sense of division and unfairness, creating hurt, anger and unrest. Significantly, concern about this unfairness runs wide. The Britain’s Choice survey work of More In Common, undertaken at regular intervals over the past year, has shown that a clear majority of UK citizens (73%) now believe that inequality is a serious problem.[1] An even larger number are concerned that we focus too much on money and status. Over 90% of Britons support the principle that businesses receiving government support have a responsibility to society, such as paying fair wages, on-shoring jobs, reducing carbon emissions, paying their taxes in full and not using offshore tax havens to avoid paying tax. There is also remarkable common ground on the need for more action to protect the environment and address climate change, with 74% believing that ‘working together to protect the environment could build a society that’s based on sharing not selfishness, community not division’.[2] In thinking about the kind of economy we choose, all of us need to place ourselves firmly on the right side of history on these major issues or we risk either political irrelevance or moral destitution, likely both.

Undoubtedly, the Conservative emphasis on levelling up is an attempt, if not to address, then at least to appropriate the concerns about inequality and belonging to their agenda. The prescription, however, embeds their response firmly in the existing paradigm rather than challenging it — the need for ‘levelling up’ is no less pejorative than its counterpart ‘the left behind’. Both phrases have echoes of the vertical conceptualisation of countries as ‘developed’ or ‘underdeveloped’.[3] The effect is to highlight what places apparently ‘lack’ and celebrate what others have gained as ‘progress’ — often ignoring or downplaying the negative consequences of that progress. On the ground, in these places, it feels insulting, demeaning and disempowering.

Any economic story told locally must be able to respond to these concerns: it must counter illiberal populism; it must fit within a civic not ethnic effort at nation-building; it must offer an alternative to financialised, rentier, neoliberal capitalism and its resultant inequality; it must reflect and respond to the climate emergency; it must be relational not transactional; and it must acknowledge and respect rather than dismiss and demean the core values expressed by people living in communities country-wide. It must, in short, answer the four challenges noted above.

This is a tough set of challenges. The lens offered here in addressing them is a grounded, local one, but what it reveals is that new futures are possible if the system is reimagined and if the economy we choose responds to social, environmental and cultural justice rather than just efficiency, profit, wealth. This really matters here in the town in which I am based — the small coastal town of Watchet, in West Somerset. The area has among the lowest wages in the UK, the lowest SME productivity and, most worryingly, the lowest social mobility in the whole country. This means that young, disadvantaged people growing up here have the least chance of changing their futures than those living anywhere else in the UK. By way of illustration, only 26% of our school leavers go to university, compared to around 50% nationally.

In some significant part, this reflects the structure of the local economy. Watchet is a small, beautiful, slightly gritty, coastal town with an industrial history, but surrounded by perfect Exmoor villages full of second homes. Its defining industry for the last 250 years was papermaking, initially in hand-made mills, but over quarter of a millennia developing into a substantial heavy industry paper mill — taking waste resources, initially rags, and later waste paper and cardboard, and making new products from them. In 2015, however, now owned by a FTSE100 company, the mill became victim to a global market in which an isolated plant in Somerset, too far from the motorway, could no longer efficiently compete, and the mill was closed, with very little notice — on Christmas Eve 2015. Close to 180 men and women lost their jobs overnight. In some sense, the town lost its defining purpose.

The conversations then and since about what the Mill meant to the community were not about jobs and wages but about meaning, belonging and connection. The men working there, and it was mainly men, don’t talk of their economic role as a means to an end, but about the value it gave to their lives. This emotive response is reflected in many post-industrial communities, as explored in John Tomaney’s recently published study of Sacriston which discusses loss and decline as a key part of the experience.[4] Similarly, Deborah Mattinson’s [5] work has explored how the loss of industries and associated community belonging is described in terms of grief and resentment — a personal and emotional response to economic change, but given extra salience by being experienced collectively and impacting identities.

These yearnings reflect the three dimensions of attachment that are central to viewing economics through a community lens — these are attachments to place, attachments to people and attachments through time.[6] Each interacts with and informs the others. As is well-recognised, place-based attachments are a near universal feature of the human experience — giving us roots, directly connecting us to the environment in which we live and grounding our experiences in territory that we call home. Although the notion of attachment to some form of place is simple enough, explaining attachments in terms of scale is unhelpfully complex. In the UK, it is layered through with competing ethnic as well as emergent socio-civic alternative national forms of identity. Most place-based identities also substantially have an economic dimension — informed over time by functional economic and social relations in an area. Attachments to place can be city-scale, occasionally county-size (though not often and predominantly reflecting economic peripherality, such as in Cornwall and Yorkshire, for example) or a host of other scales and dimensions — from the tight-knit village to amorphous and ill-defined geographical areas that may or may not cross-cut contemporary administrative boundaries.

The importance of attachments through time reflects ancestry and shared histories of the places we inhabit, but also, crucially, our commitment to those who follow on after us. Although they appear backward-looking, efforts to protect special features in places (buildings, landscapes, culture) are an act of saving, not for the past but for the future. It represents a care being taken for those that are not yet born or have not yet moved in. The same is true of community development. In hundreds of consultations up and down the country over the last ten years, we have asked people from diverse backgrounds and in very different contexts, what motivates them to contribute to the community. Despite the assumption of Nimbyism, parochialism, nostalgia as incentives, by far the most commonly cited reason for community action is not to hold things back but to create change, to build a better future for generations who will follow. This commitment across time in both directions — an attachment to descendants not just ancestors, connected to place and nature — offers a mechanism for widespread action on climate — a stewardship of the places we love for future generations.

The third area of attachment is the relational — attachment to people. It is this attachment that animates and personalises our experience of place and through which it evolves. Place is not static, it is ever-changing, constantly updating, endlessly refreshing — and it does so primarily through our connections, attachments and relationships with people. These three attachments taken together create community — nothing more complex than people in a place through time. It is through community that we feel rooted and secure; through community that we belong.

For much of its existence in Watchet, the paper mill as a business, hosted locally, cultivated those attachments and connected them to economic intent. The mill was about industrial production but it also built and cared for a community. This is not to romanticise the incentives of the industrialists,[7] but regardless, for hundreds of years the owners made the connection between their economic role and a wider societal one. In towns up and down the country, industrialists helped to create the built environment — building housing, libraries, public halls, chapels and much more. Beyond that contribution to the built physical infrastructure, the contribution was also to community life. The mill in Watchet cultivated and animated the social infrastructure which kept people connected and secure and it contributed to a sense of shared history, identity and meaning that stretched across generations. As in Sacriston, ‘economic and community vitality were inextricably linked’ and the ‘strong local economy was a key underpinning for a strong community’.[8] Working in attached companies helped to create more than just jobs but rather decent and meaningful jobs which meant people felt value, connection and agency in their work — some sense of control, if you like. By contrast, recent decades have witnessed a withering of interlinkages between economic and community life and an associated reduction in purpose and belonging, which has been cynically manipulated in the rise of a politics with populist and nationalist appeal that blames technological change, globalisation and immigration, whilst furthering the neoliberal cause.

As the state stepped into social functions through the decades post-war and free market reforms were instituted through the 80s and normalised in the 1990s, the private sector was able or encouraged to retreat from societal responsibilities, turning this relational interdependence into a transactional relationship — one which is, relatedly and significantly, often also an extractive one. This has been further accompanied by, and/or reflects, a focus on individualism and consumerism that has extended out from its market base to influence interactions in the public and civil society sectors. Compounding this, since the 2008 crash, in many ‘left behind’ places, as austerity has bitten hard, we have seen an ever-wider gap between what the market cares about and what the local state can afford or is empowered to provide. People in these places remain viscerally affected by the economic system they live within and the modes of employment and values it conveys, but have almost no say in its development, trajectory or purpose — they are no longer attached in a meaningful way to a national economic story.

We can all recognise the uncomfortable truth that we care more intently about those living nearby than those in far-away lands. The social and emotional connections that makes us care and make us human are very often place-based not just people-based.[9] Yet, over time, these changes have released large parts of the economy from the attachments to community that had in some way acted as a constraint, even where they remain hosted in communities (private equity-owned care homes and retail property being the most obvious examples, responding to short-term financial rewards for shareholders over service or purpose). The community-hosted businesses of old, epitomised by Watchet’s mill, linked these connections with economic power, tying business firmly to place, to people, to one another. In part, and again without meaning to romanticise, these ties demonstrated the power of community to overcome, resist and check the damaging consequences of inequality and suffering that can happen when economic power rests elsewhere. And they pointed to the mechanisms that hold us together — trust, reciprocity, solidarity, care, friendship, culture, identity. In particular, from the experience of places like Watchet, the importance of social capital is revealed — as a critical part of what enables us to survive, protect and connect the vulnerable in the face of social and economic shocks — from future pandemics to climate catastrophe.

Covid-19 highlighted powerfully that community is a foundation of that resilience. It is a layer of infrastructure that steps in when all else fails, and which is critical to the effective functioning of both market and state infrastructures. Faced with immediate needs, strong communities proved able to cooperate, innovate and provide solutions in a distributed way, often faster, smarter and at lower cost than either the centralised state or the disconnected market. For example, during the first lockdown, while many vulnerable people continued to wait for costly, slow, centralised systems to act, strong, well-linked communities rapidly re-deployed resources and developed mechanisms, networks and processes to help — setting up phone lines, training volunteers, providing technology, enabling payments, delivering essential food and medicine, and offering emotional support. The duality, if there was one, between those involved in this effort and those not, was primarily one of attachment — many of the crucial actors were private sector, working alongside community. Local publicans repurposed their kitchens to provide meals for the elderly and those isolating. Greengrocers delivered parcels to doorsteps. There are far more economic players acting with ‘purpose’ than the dominant narrative would have us believe. In all this, it was social capital, in which repeated community interactions build trust, reliability and reciprocity, that made communities capable of organising themselves. Cross-cutting sectors, it had the effect of reducing the transaction costs associated with more formal coordination — meaning communities were able to ‘move at the speed of trust’ to protect those most at risk.[10] With lives on the line, the benefits of being able to do this without needing a more time-consuming, costly, contract negotiation were self-evident. Those benefits also exist in more normal times.

The expansion of government’s role in the economy post-Covid is probably inevitable. Consequently, it is more vital than ever to make an impassioned case for decentralised alternatives that build on the strengths demonstrated during Covid. Despite some progressive examples[11], the weight of the narrative appears to be pushing towards a state capitalist response as a counterpoint to the market’s failings, rather than one founded on mutuality, community and distributed structures. This brings risks around centralisation and disempowerment — undoing rather than supporting much of the place-based and community-responsive energy of the last two decades. This is not aided by the fact that within serious economic analyses, community conceptions are only weakly articulated.

On the right, community holds obvious appeal as a counterpoint to a larger state, but policy suggestions thus far have been frustratingly two-dimensional. The approach of Onward, for example, sometimes feels like an attempt to buy-off communities through transactional bargaining (the suggestion of payments for completing the maternity red books and the offer of civic sabbaticals for those rich enough to take them are perhaps the most troubling)[12]. Danny Kruger’s insightful and intelligent analysis of the problem as an economic as much as social one, in his recent review, ended nonetheless in constrained policy prescriptions. It focused mainly on support for charities and incentives for volunteering, alongside relatively small pots of money to enable more community-based activity — perhaps more tinkering than serious economic reform. Though, to be fair to Danny, who is a powerful advocate for the need to rebuild social fabric and connect it to the economy, the challenge within the Conservative Party is a longer-term one.

The ‘community paradigm’ work of New Local (formerly NLGN)[13] to bring Elinor Ostrom’s community-focused economics into the mainstream offers a more substantive effort at reimagining macroeconomic structures and institutions as poly-centric, network, self-governing mechanisms. It could begin to tip the balance and demonstrate an alternative conception of community economic development with wide appeal, though how much it really challenges the existing paradigm also remains a question of debate. Ostrom explored how small, self-governing communities were nearly always better at resolving thorny social and economic problems than either markets or states, a position reinforced by the already referenced rapid community mobilisation in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Other economic analyses that explore stewardship capitalism, creative capitalism and ‘the Commons’ as a functional system also offer value and insight, as of course does the foundational economy of Karel Williams amongst others, as well as the behavioural economics discipline, with its rejection of the rational man and its acknowledgement that humans value and prioritise a whole range of things in their economic decisions over and above profit and wealth.

Perhaps most aligned to a new people-centred economic future is Kate Raworth’s ‘Doughnut Economics’.[14] She argues that the aim of economic activity should be meeting the needs of all within the means of the planet, with a driving imperative to enable human and planetary flourishing rather than growth. Here, the importance of people is paramount. Raworth asks us to change our view of what we want to be, with a focus on a distributive, non-linear, regenerative model, but leaves the potential of networked and collective models of economic activity, and the power of attachment in constraining excess and providing meaning, under-examined.

The ‘diverse’ or ‘community’ economies work of Gibson-Graham, and others who have followed, is also valuable.[15] It constitutes a similar revaluing of what our economy is for — in which our interdependence with each other and the planet are put centre stage. It would lead us to speak of an economy that extends beyond even those ignored or providential parts of the formal economy captured by foundational narratives; and to incorporate the diversity and multiplicity of economic actors and activities that exist in alternative capitalist and non-capitalist forms. Such an approach, for example, recognises the economic value of the unpaid work of child- or elderly-care, the work of community activists that build trust and belonging, and the practices of social enterprises, community cooperatives, purpose-driven firms and traditional charities that are motivated not by profit but by a commitment to social or environmental wellbeing. It also acknowledges that these alternative forms of economic activity support the foundations that allow the prevailing economic system to function, and/or provide the sticking plasters when it fails. A community economies lens also moves the economic conversation from one that is characterised as a struggle between competing forces or competition for the spoils — whether between the left-behind and the got-ahead, the growth sectors and the forgotten ones, those driving progress and those receiving redistributed benefits, or between ‘traditional’ and multi-cultural communities. Instead, it brings to the fore modes of thinking and being that reflect the values uncovered in communities of all kinds and that are the underpinnings of place-based approaches. A community economies lens reframes what is valued — normalising not an extractive structure, made up of self-interested individuals that value profit, but one that is regenerative, made up of connected, social beings that value wellbeing and the planet.

It also has the very significant merit of including far more of us in the story. To quote the feminist philosopher Donna J Haraway: ‘it matters which systems systemise systems. […] It matters which thinkers think’. [16] Who participates in the economy matters, whether that is as workers, consumers, business owners or as ‘communities’. Yet so often, the potential role of ordinary voices in making change seems to be largely overlooked [17], despite having a wealth of insight to offer, as reflected in Marc Stears recent exposition.[18] The disenfranchised and most-negatively-affected largely remain that way, without access or a voice. Hearing people describing their alternative future is the first step in recognising that better is possible. In a recent process of community imagining in Watchet, for example, we explored with a diverse group of townsfolk what a future economics would look like. Mostly people describe very similar things. Namely; a greater connection to nature; human activity that does not harm the planet; greater togetherness and spaces to meet and be together so that no one is lonely; and decision-making systems where they are a part of the decisions being taken. Over and over people yearn for a version of these four relatively simple things.

And yet community — and the place, time and people attachments which form it — is not taken seriously as an economic force. Community is regarded as gentle, fluffy but distinctly amateur, or as parochial, reactionary, backward-looking — the opposite of the ‘progress’ to which we aspire. In fact, on the ground in communities, whether facing the threat of a pandemic or otherwise, community has proved itself endlessly powerful — adaptive, kind, enveloping, but also fierce in its compassion. In the absence of the ‘normal’ economy, with everything non-essential closed, we saw clearly the value of our social infrastructure. In Watchet, as elsewhere, and especially in many ‘left behind’ places, it was an interconnected social ecology, built on trust, shared value, common purpose, built on knowing each other and caring about each other, that was able to react and find new ways that worked. Three values stand out — each anything but parochial. They are compassion for others, curiosity to find new ways and learn about one another, and solidarity across divisions. In many ways, place-based attachments are the opposite of exclusionary — community is universalising of difference, giving us a concern for one another built on nothing more than that we happen to inhabit the same land — the very definition of a civic identity.

What then does a national economic model look like if community and attachment is taken seriously? If the values sought are the ones we find in communities — of social and environmental (even cultural) justice? What if the functional structures of the economy are communities (of place and shared identity) rather than the firm or the individual and if key resources are the attachments, networks and trust that create social capital rather than only physical, financial and human capital? What happens at a much larger scale if communities rather than the private sector own the means of production? What if financial flows are not predominantly private and shareholder-delivered, whether through publicly-traded or equity models, but instead have some communal or stakeholder foundation? What if traditionally state-centric systems (like education, health and social care) are also entirely reconceived as decentralised, distributed and disbursed?

These are each potentially expansive and radical areas of policy exploration within a framework where the state has a bigger role but in creating the institutional and regulatory structures that would enable a distributed, local, attached economy to emerge. The simplest intervention as others, Haldane included, have mooted, is investment in social (and cultural which is just as important though it barely gets mentioned) infrastructure. To make any in-roads, it is critical that this is not watered down to mean basically anything that is not physical infrastructure. The focus must be on places, organisations and practices that encourage, embed and broaden attachments. This can include all kinds of places from post-offices, pubs, shops, community centres, art galleries, parks, and it can include much of the public sector — nurseries, schools, hospitals, — but these are all only social infrastructure if they build opportunities for associational life. Schools, for example, are often entirely detached from community life, hospitals too; and pubs can be the most exclusionary of all places. It’s not a catch-all. The practice matters.

This means that alongside investment in physical social infrastructure, there is a need for investment in the practice of building and sustaining community. Borrowing from Hannah Smith, we call this the craft of connectorship.[19] It reflects that community is hard — people are complex, messy, difficult, and relationships are works of empathy and patience, especially where money and power are involved. There’s no easy fix here. Building community, especially where it has been destroyed and people are fearful, takes time and energy and funds. Social capital can be tightly bonded, exclusionary and tribal as much as it can be bridging, open and supportive. But this is the work of relational policy. As Smith writes: ‘So much is written and understood about the science and art of entrepreneurship. It is studied, funded, supported, held up as an economic engine and a pillar of strength. The entrepreneur is seen as an alchemist — a spinner of gold from rare reserves of ideas, energy and dogged determination. Imagine if connectorship occupied a similar place in our consciousness. ‘Connectors’ as the weavers of all the untapped potential hidden between people and organisations. With the same commitment to purpose, but through nourishing whole systems instead of single organisations.’ [20]

With connectorship, the need for concerted investment also relates to a commitment to widespread engagement and participation in community visioning for new economic futures. This is not about ‘all the conversations’ but it is about conversations with a diversity of voices — giving voice to the unheard and ‘hard to engage’. Communities of place become communities of interest through shared visioning about the futures they want. It is this that allows the universalising of difference that is vital in any civic identification of an economic story — local or national, and it is only by working at it that we can distribute agency.

The focus on ‘community’ rather than ‘local’ matters here too. In the US in fact, as Greenham and Boyle describe in their excellent booklet on ultra-local responses to places bypassed by the global economy, the narrative is much more about ‘self-reliance’ than it is about ‘local’. ‘Self-reliance is not isolation. It is diversification, and it is through diversification that we are building wealth’.[21] Two important distinctions are conveyed, about the central actors — not the local state but local people — and about agency — communities are the actors themselves not the subjects of others’ efforts. The role of local government then shifts to more of an enabling model. I am often asked what local government can do to support more community economic development. My answer is usually some or other form of: ‘it can help get the obstacles out of the way’. Post-austerity, the capacity of local government to act has been hollowed out more than ever leaving their resourcing dominated by statutory services, predominantly adult and children’s social care. Nonetheless, local government with little resource to act in economic development, retains an impressive ability to prevent anyone else acting in its place. An attitudinal shift is needed.

Where local government is embracing its role as enabler and partner in community economic development — cities like Plymouth, Liverpool, Bristol — we see real impact, and a key role in supporting two things which communities tend to lack — an ability to underwrite risk and access to finance. Notwithstanding the debate about whether to substantially re-resource local government, it is vital therefore that no revival of local government’s standing should be used, intentionally or otherwise, as a mechanism by which to flatten the seedlings of the emergent ‘fourth sector’ of purpose-driven, often community-led, organisational forms. This requires a genuine culture shift in local government and a genuine acknowledgement by politicians on all sides that if the ambition is to reconnect with all those not obviously benefiting from the prevailing system then communities are not just conveniently placed, but better suited, to delivering meaningful change in economic agency. There is already a palpable sense of frustration in communities which are not lucky enough to have ‘progressive’ local authorities and which are, consequently, being held back. The risk is of a new duality emerging — between places where local government ‘gets’ its enabling role and places where it instead acts to constrain. There is a latent danger that we’ll end up with a new dividing line — a different group, or worse, the same group of places, pushed even further behind.

In considering the role of local government too, the primary gap that needs attention is not one of political agency and connection (though that warrants its own conversation) but one of economic agency and attachment. This is not about building a more relational polity through local government reforms, to sit alongside unreformed transactional economic relationships. Reforms that give people more say in economics are needed. This inevitably means a more radical economic agenda in which institutional structures and regulatory tools are adapted to support an economy built on distributed local power that is relevant to people’s attachments to place and people, over time.

In places that have long been ignored by the market or where the state has historically played a smaller role — often the more rural or peripheral — alternative models have already emerged. The answers provided in these places, as well as the problems they face, tell us how the economy is already being reshaped, where reform is most needed, and perhaps most importantly, what could follow in the years to come. What we find are powerful examples of people working collectively to regain economic agency and to build community economies that support and nourish life. ‘There is no shortage of examples of alternative economic organisations and practices that are creating socially and environmentally sustainable community economies.’[22] In Plymouth, for example, there is a city-wide effort to rethink economic models to address the prevailing imbalance, by supporting active citizens, robust communities and more purposeful businesses. Building on the experience and learning from cities like Barcelona and Cleveland in the US, Plymouth is seeking to develop a vibrant, greener and fairer economy. ‘Using concepts like municipalism, community wealth building and social value; and economic models such as social enterprise, community business and co-operatives; determined activists are creating alternative forms of power to advance and expand a more democratic, regenerative economy. People are building powerful communities with greener, economic democracy at the core.’ [23] This new model of an engaged, distributed, local economy is driven by partnership between Plymouth social enterprise network, the local council, the world’s first certified social enterprise university and an engaged private sector.[24]

In Plymouth as elsewhere, it is important to recognise that these efforts at community enterprise are not seen by sector leaders as only a symbiotic solution to market failures in the current free or pro-market, neoliberal system but instead as a demonstrable way to replace it with something different. These leaders are grappling with the major social ills of our time — from social fragmentation to environmental pressures to economic restructuring and global volatility. They want to be a part of building a new, better future, within an economic settlement that prizes social, human or environmental value over financial value or which disputes the organising principle of profit.[25] They do so by incorporating attachment in some form into their business models and are committed to economic priorities being decided and owned locally, at scales adapted to suit place-based attachments.

Across the media too, during Covid-19, there has been a powerful acknowledgement of the ideas on which much of the community enterprise movement is founded: that we are more together than alone; that our social nature is a source of strength and purpose; that community connectedness is a valuable resource and that expertise, efficiency, enterprise and innovation do not have to come at the expense of what matters most to us as connected, caring, creative people. With the brittleness of the prevailing system shown only too clearly, what emerges is an opportunity to reimagine the economy as one built on values other than growth and profit. The shift in discourse to a values-based economy has picked up steam, with leader writers in broadsheets from the FT to the Guardian, and powerful institutional voices such as Mark Carney and Andy Haldane recognising that a different way may be both necessary and possible. This signals a marked shift — a very public recognition of the failings of the system and the values on which it is based: that social, economic and environmental justice need to be more readily embedded in the new normal.

The policy prescriptions that fall out are complex and wide-ranging and get to the heart of economic frameworks — challenging norms of ownership, governance, resourcing and motivation. For example, there is a gentle impetus towards bringing community more into high street revival, with even absentee landlords seeing the immediate benefit of engaging as a way to fill empty properties — but a meaningful shift would mean moving say 30% of high street properties into community ownership over time, so that gains can be secured for the long-term.[26] Potential levers exist — every private sector beneficiary of the string of regeneration and ‘levelling up’ funds that are in the offing could be required to give up some equity to the community in exchange — an entirely normal transaction in equity investment, and common in recent bailouts by national government.[27] Such a move would attach communities to the businesses that affect them and give them a long-term stake in the relationship, as well as providing ongoing financing for improvements in their areas. Government tax rules could prioritise rather than penalise social enterprises and community businesses — cutting corporation tax to zero for companies that are purpose- rather than profit-driven. Forms of steward-ownership could be promoted — in Denmark, 60% of publicly-floated companies are in some such form — they are more resilient, less likely to fail and provide more stable employment as a result. Networked systems of financing for local businesses could be decentralised through local financial institutions or local economy preservation funds, addressing the substantial market failure in the capital markets that constrains locally-hosted companies from investing in their places.[28]

In all such prescriptions, the intent is to root economic decision-making and economic benefits more locally — ownership structures, management cultures, social impact and profit distribution become ‘closely knitted to host communities’, as in foundational ideas. But in this, neither the sector nor the prevailing conditions should be the determining factor in the reframing — this is not a prescription for just providential parts of the economy or places where the current model is failing. Companies operating high tech or R&D intensive work can be as much a part of an attached economy as any other, and that attachment does not have to come with any ‘peripheral’ connotations. The example in Watchet is instructive here. When the Mill closed, we wanted to avoid the slide into decline of so many other places that had lost their defining industry. Through a period of intensive research that asked the community what they wanted for a new future and explored possible industrial but environmentally-sustainable futures, we looked for options for a new community industry to replace the one lost. In partnership with London-based biotech start-up, Biohm, we are now co-creating the world’s first community-centred bio-manufacturing plant — using mycelium (the roots of a mushroom) to turn local waste into new carbon-negative products to sell to the construction sector, just as we once turned rags into paper. What is powerful is how this model embraces a circular approach to community. It attempts to put the people most affected at the heart of industrial innovation, and to ensure that their needs are centre stage in the economic relationship so that it cannot become exploitative or extractive of them as individuals, or as a community.

This also means finding a way to get ownership into community hands — away from the real estate asset bubble that values property not in terms of its service or productive use but as an asset class, with investment driven only by the prospect of future financial gains. To tackle this, we are seeking to protect and reintegrate industry and economy by means of community ownership and stewardship of our assets. The profits from the facility will be split 50:50 between Biohm and Onion Collective — with our part reinvested in the kinds of social and cultural infrastructures that have been stripped away by the impoverished state but that support and enrich our lives — from educational work, to art and culture, to public space for local people to meet. This is about reprioritising the productive economy locally: creating a more resilient, more effective model which combines an emphasis on low-carbon circular, regenerative resource use with one that is also regenerative of communities, as the first line of defence of the vulnerable, and as a vital building block in a distributed, local and participatory economy.

Undoubtedly, in all this, it remains the entrepreneurial spirit, a core foundation of the capitalist narrative, which characterises many of the most vibrant community enterprises. But what is also evident is that innovation in communities can be as much driven by a concern to maximise social impact as to maximise profit; questioning a central tenet of the traditional narrative that profit primarily drives innovation.[29] Against this backdrop, community enterprise emerges as a part of a ‘radically more inclusive and democratic way to run local economies’.[30] The need to reframe the national economy is not merely in terms of an everyday economy, but also about the everyday entrepreneurs. They can and are playing a role in building a brighter, distributed, attached economic future in places all across the UK, no matter what the conditions of their present reality. They have often been ‘ignored’, or ‘forgotten’ or perhaps, thankfully even, ‘left alone’ by the prevailing system, but they have thus become more boldly independent, more innovative, and have more deeply embedded community values. These are the places that point the way forward, where there is real drive to address inequality and environmental crisis. The playing field does not need to be ‘levelled’ for them, it needs to be ‘tilted heavily’ in favour of a more distributed, more attached and more inclusive economy that reflects a different perspective on ‘progress’. A narrative of many more of us as everyday pioneers for a more socially and environmentally just future can create an antidote to division and illiberalism — based on belonging, connection and hope.

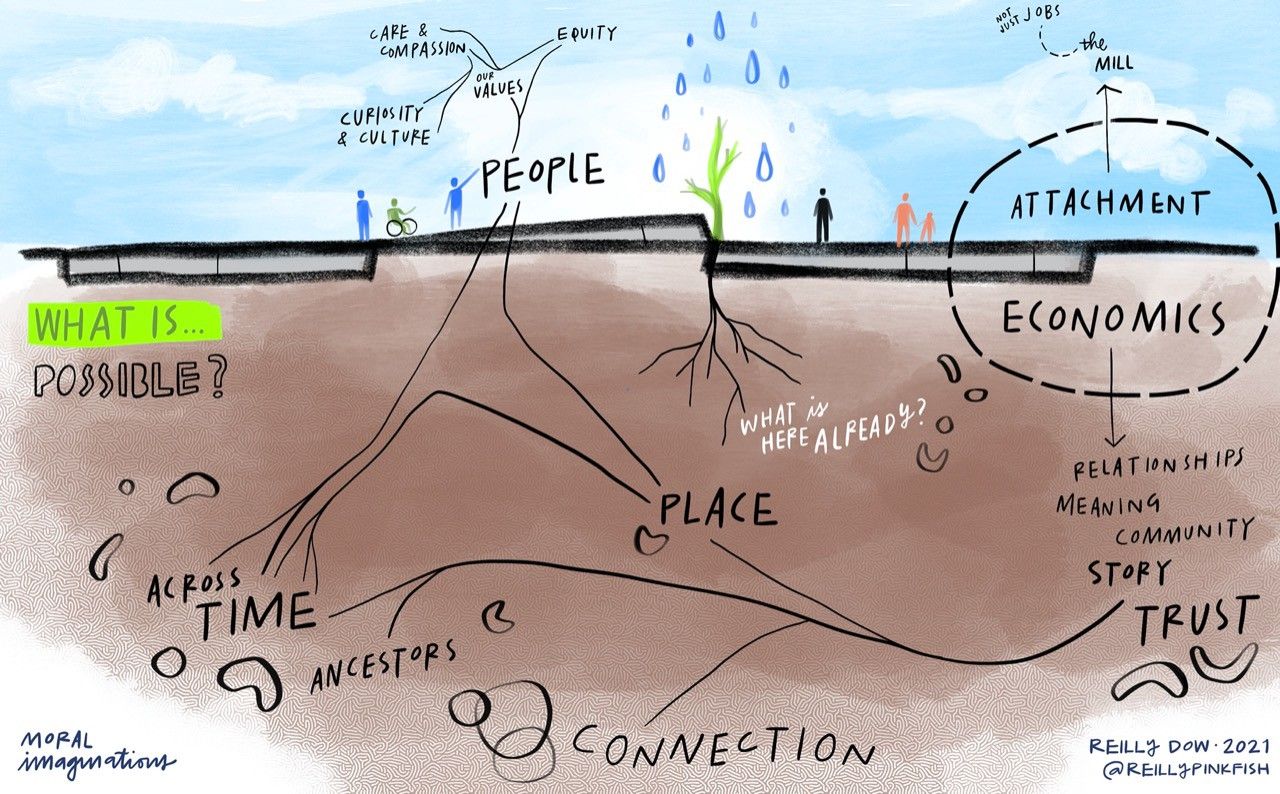

During 2021, supported by the National Lottery’s Emerging Futures Fund and by Power to Change, Onion Collective are working with community entrepreneurs from across the country to write a book about the economics of attachment, bringing new ideas about how we can reclaim and reform economics through values that guide community — curiosity, compassion and solidarity. The Collective is also working with Phoebe Tickell and the Moral Imaginations team to explore community narratives of the next economy. Please get in touch with Onion Collective if you are interested in this work and its publication.

The main illustration for this essay is by Reilly Dow and was created as part of the Watchet Moral Imaginations Lab.

[1] More in Common, Britain’s Choice: Common Ground and Division in 2020s Britain, October 2020, https://www.britainschoice.uk/

[2] Laurence Tubiana, Welcome to the green industrial revolution, the Telegraph, 25 November 2020, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/how-to-be-green/un-climate-change-summit/

[3] J K Gibson-Graham, Jenny Cameron and Stephen Healy, Take Back the Economy, University of Minnesota Press, 2013, p.9.

[4] John Tomaney, Lucy Natarajan and Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite, Sacriston: towards a deeper understanding of place, UCL, 2021

[5] Deborah Mattinson, Beyond the Red Wall: Why Labour Lost, How the Conservatives Won and What Will Happen Next?, Biteback Publishing, 2020

[6] My thanks especially to Jess Steele and Carolyn Hassan for highlighting the particular lens of time as instructive.

[7] Incentives were driven by the church and practicalities as much as anything.

[8] John Tomaney, Lucy Natarajan and Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite, Sacriston: towards a deeper understanding of place, UCL, 2021, p.4.

[9] W Norman, Adapting to change: the role of community resilience, 2012

[10] Iain Chambers, Make do: Travelling at the speed of trust, 7th April 2020, https://www.thebevy.co.uk/2020/04/07/make-d0-travelling-at-the-speed-of-trust/

[11] In Amsterdam, for example, local government is adapting a city-wide approach built on Kate Raworth’s ‘doughnut’ macro-economic remodelling of the system.

[12] Will Tanner, James O’Shaughnessy, Fjolla Krasniqi, The policies of belonging, Onward, 2021

[13] Adam Lent and Jessica Studdert, The Community Paradigm, 2019, https://www.newlocal.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/The-Community-Paradigm_New-Local.pdf

[14] Kate Raworth, Doughnut Economics, Random House, 2017

[15] See, for example, Community Economy, by the Community Economy Collective, included in Keywords in Radical Geography: Antipode at 50, First Edition. Edited by the Antipode Editorial Collective, 2019, John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

[16] Donna J Haraway, Staying with the Trouble (Experimental Futures): Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Duke University Press Books, 2016, p.101

[17] Mary Hodgson, A tale of two cities: community perspectives and narratives on inequality, struggle, hope and

change, The Young Foundation, 2017, https://www.youngfoundation.org/publications/tale-two-cities/2017

[18] Marc Stears, Out of the Ordinary : How Everyday Life Inspired a Nation and How It Can Again, 2021

[19] Hannah Smith, An Enquiry: On What Lies Between, https://medium.com/thepointpeople/an-enquiry-on-what-lies-between-9a66ba88ad29, 2020

[20] Ibid.

[21] David Boyle and Tony Greenham, People Powered Prosperity: Ultra Local Approaches to Making Poorer Places Wealthier, New Weather Institute, 2015, p.24

[22] J K Gibson-Graham, Jenny Cameron and Stephen Healy, Take Back the Economy, University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

[23] Gareth Hart and Ed Whitelaw, Powerful Communities and Economic Democracy, 2021, https://plymsocent.org.uk/the-state-of-us-2021/

[24] A conference being held over four days in April and May 2021 will explore this experiment in economic democracy. https://realideas.org/about-us/our-work/state-of-us/

[25] At two symposiums held by Onion Collective in Somerset and Halifax in 2018 with community business leaders, economic motivations cited included: ‘Systemic economic change’, ‘failure of the current system’, ‘spreading economic power’, anti-capitalism’, ‘interaction with global questions on a local effective scale’, ‘nondependence’, and ‘anti-individualist’. The only ‘business’-related responses were to discuss ‘business’ as a way of achieving these goals (and others related to agency, connectedness, fairness primarily) — as a ‘vehicle’ or ‘better tool’ for driving change that gave power to community actors.

[26] With thanks to Rebecca Trevalyan for this policy ambition.

[27] With thanks to Hannah Sloggett and Wendy Hart of Nudge Community Builders for this idea.

[28] As Greenham and Boyle discuss, more than half of employment and value added comes from SMEs in England, but they get much less than half of capital investment, an obvious market failure. Ibid, p.78.

[29] Mariana Mazzucato, of course, has also argued that the state too is a driver of innovation, again counter to the traditional narrative.

[30] Forum for the Future, Community Enterprise in 2030, Draft, 2018.